This blog is a first person account of my experiences of working in authentic Reggio Emilia, Italy ateliers with the atelieristas who originally created them during the 2013 international study group, Atelier, Creativity, and Citizenship: The Culture of the Atelier between Thinking and Acting sponsored by the Reggio Children organization. Under the watchful and encouraging eyes of the atelieristas I was able to acquire a more in-depth understanding of the Reggio approach to working intensively with art in the studio. My observations of these ateliers have influenced my understanding of the Reggio approach, and in particular, has inspired my ideas for music studio provocations with children.

Atelier Experiences at the Loris Malaguzzi Centre December, 2013

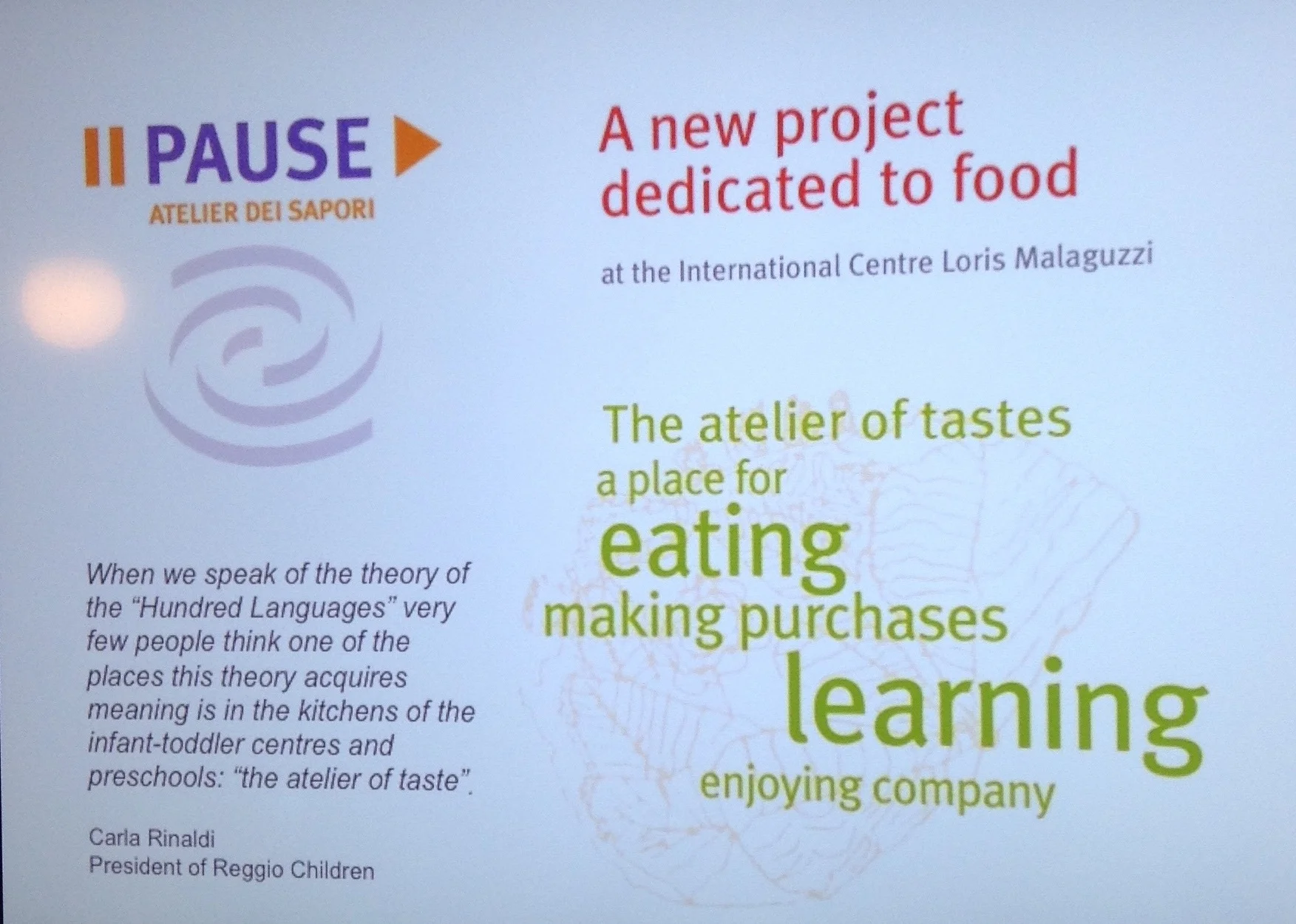

The international study group began on a Sunday evening at the Reggio Children Loris Malaguzzi Centre. To our surprise, upon arrival we were given aprons and hairnets and told to wash our hands to prepare for our first atelier experience. The Languages of Food Atelier: Variations of Pasta was the beginning of our atelier study group experience.

The Reggio school’s cooks, dressed in white dresses and hairnets, welcomed us with smiles and traditional Italian kisses on the cheeks. Standing besides them were long stainless steel tables filled with various tools and food items. We were split into small groups and guided in the first steps of making pasta from scratch. The cooks demonstrated for us how to nest a raw egg in a pile of semolina flour and then knead it into pasta dough. After the cooks demonstrated this technique, it was our turn to do so. In this first immersion atelier experience, for three hours we kneaded, rolled, sliced, stuffed, and flavored at least fifty different pastas.

To my surprise, I was struck that this atelier was not simply a free exploration experience as I expected. On the contrary, we were guided in learning specific techniques by experts in that area and then encouraged to practice and demonstrate our skills. Some of my questions were already beginning to be answered. The philosophy of the atelier was readily apparent: It was a hands-on learning experience, requiring minimal instruction, and lots of trial and error. The atelier was also a social learning experience; we helped each other during the process and only asked for guidance from the cooks when we were completely lost. The result was a beautiful array of handmade authentic pastas. “Why is our first experience of the atelier making pasta?” I asked. Because food, we were told by the group leaders, is one of the most beautiful human experiences people can share. Italians, of course, take their food very seriously. Even the preschool lunches at Reggio schools are one hour long. The children are involved in the preparation of lunch, including helping the cooks, setting the dining ware, and decorating the tables. The food is healthy and delicious, served over multiple courses; lunchtime is a ritual, one example of the care and quality afforded to many aspects that are central to the Reggio schools.

The next day study group participants were split into small groups in order to experience various ateliers as the children might experience them. Five ateliers were staged for our participation: 1) Ray of Light, 2) Digital Landscapes, 3) The Human Figure Between Bi-dimensional and Tri-dimensional, 4) The Secrets of Paper, 5) The Life of Living Organisms: Faded Beauty.

The first atelier that I explored was Digital Landscapes. Guided by the atelieristas who created it and have worked with children in that atelier, participants were asked to walk around the displays and interact with the materials. In this atelier the materials were projections of moving images such as fish swimming in a coral reef or ocean waves crashing onto a beach. Large and small objects were placed between the projection and the screen, which would create effects such as blocking, twisting and reflecting the projection’s images in interesting ways.

The objects were different sizes of white three-dimensional objects, mirrors, and soft building blocks of various sizes. In addition, there were colored gels and cutouts that could be applied directly to the projection device to change the color and feel of the projected images themselves.

In my small group we moved the objects around to see how that might change the “landscape.” The atelieristas observed us closely and documented what we were doing, or saying, by taking notes and photos. We were confused about what we were supposed to be doing in this atelier. When we asked for clarification, the atelieristas simply told us to enjoy exploring in any way we wished. I began to understand that by moving objects within the installations we were creating our own variations and “experiments” with the materials provided.

After some initial experimentation, I posed a “hypothesis” to the group: What might happen if we turned the video projector upside down? Would the fish then be swimming backwards? I asked the atelierista if I could turn the projector upside down, and of course, she said I was free to do so. Indeed, the result was odd; the fish looked strange in the way they were swimming though they were not really swimming backward.

For three hours we moved objects around to change the “digital landscape.” Because of my background in music, I continued to compare visual ideas with musical concepts. I shared with the group that pitch and durational relationships in music could be thought of as similar to the visual relationship between distances and sizes of the objects. For example, larger objects could represent longer durations of sounds, and smaller objects might represent shorter sounds. In addition, the distance between the objects could be considered silence (rests) between these sound events. I asked the atelierista if this was strange for me to see music in visual art? “Not at all,” she said, the “interweaving” of poetic languages is always encouraged in the atelier.

I then began thinking more seriously about music in relation to the visual perspective. I noticed that, depending on how you arranged the materials, they were either in the foreground or in the background. Music also has a foreground or background perspective. A featured instrument or voice is the “foreground” with accompaniment in the background.

At the conclusion of this atelier, all the small groups gathered with the atelieristas who shared their documentation of our work. While there were no specific learning outcomes expected, teachers and students were learning together simutaneously. The atelieristas shared what they observed from us and then solicited our perspective on the documentation they had shared with us. This was a very iterative, back-and-forth process that kept building on the ideas and observations that were discussed.

During the remainder of the week we explored the other ateliers. The Human Figure: Between Bi-dimensional and Tri-dimensional, was intentionally designed to challenge children at very complex conceptual levels. This atelier used a combination of media. There were wire and clay sculptures, photography, digital projections and live webcam images interwoven in various ways. We were prompted to explore the interrelationships between the human figure in both two and three-dimensional space.

My small group used a webcam to record original video, and then manipulated video recordings into our own unique “digital landscape.” Our group decided to point our webcam out a window into the side yard of the Malaguzzi Center. Several of us went outside and “acted” for the camera. We climbed and hung from branches in a tree, we danced, we walked backward and we made strange shapes by connecting our bodies in different ways. Using a video editing computer program to choose clips, we manipulated the images with different effects and created an original video loop for the installation. We then displayed our video and, as in the last atelier, we moved objects to reflect the projections and were able to curve and stretch the moving images in interesting ways. Using the webcam technology was both fun and powerful. Our group worked hard to complete the project in three hours, but the atelierista reminded us that there was no hurry because a final product is not the purpose of the atelier.

As in the previous atelier, the atelieristas gathered us together and shared their documentation of our work. We discussed the following questions: 1) What is the relationship between two-dimensional and three-dimensional?; 2) How is it that a flat digital image projected in space can become three-dimensional?; 3) What is the relationship between virtual and real, being and seeing, and transformation? and 4) How did graphics, photography, wire, and clay interrelate and/or blur the relationship between real and virtual boundaries?

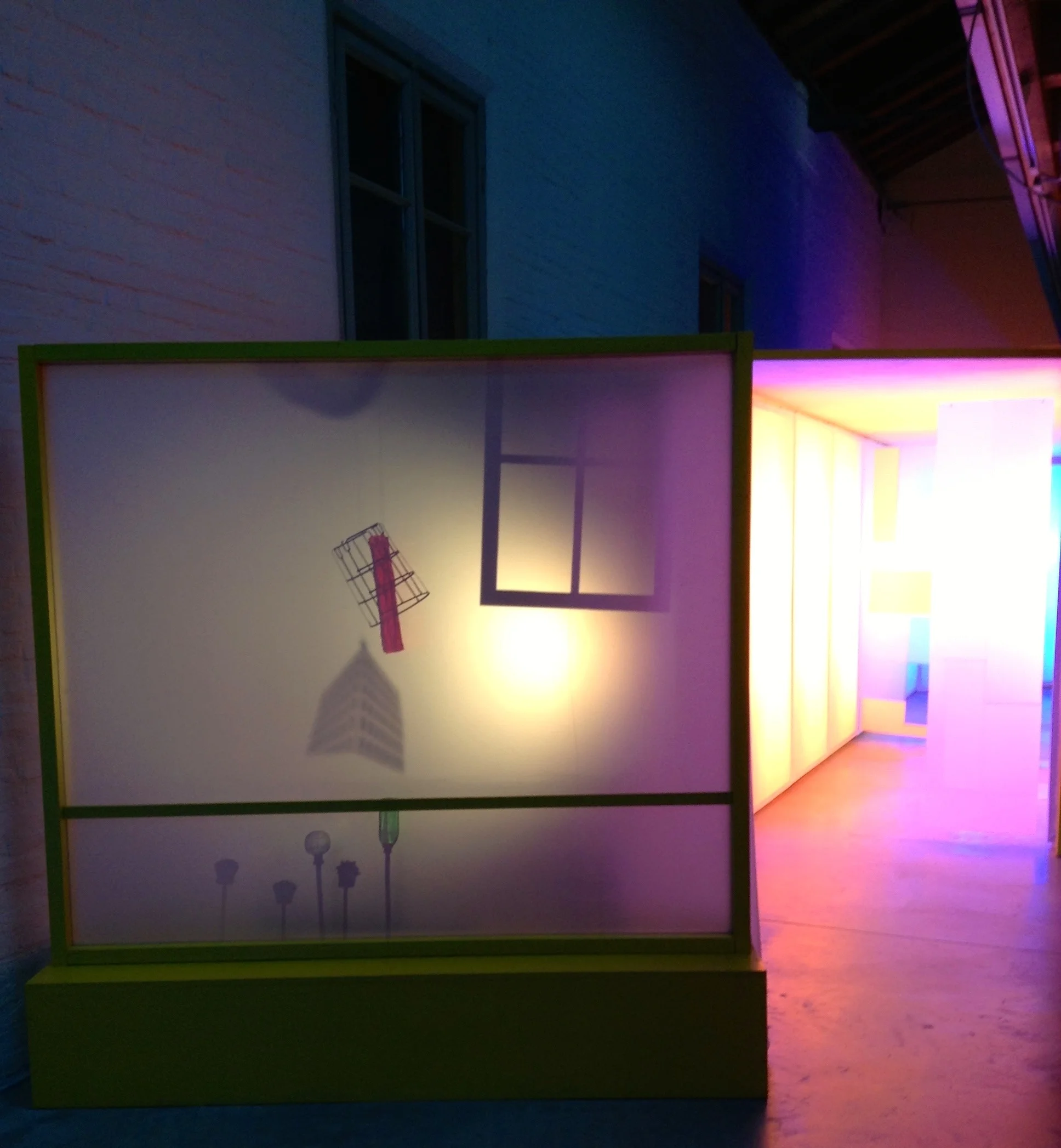

The Ray of Light was one of the most beautiful and interesting of the ateliers. Many rooms were filled with different uses of light to explore. There were numerous objects that could be moved and placed in different positions, light tables, colored light projections and labyrinth-like areas to explore. This atelier highlighted concepts related to the physics of light through a hands-on discovery processes. The atelier’s main guiding question was, “how do we interpret what is going on in front of our eyes?”

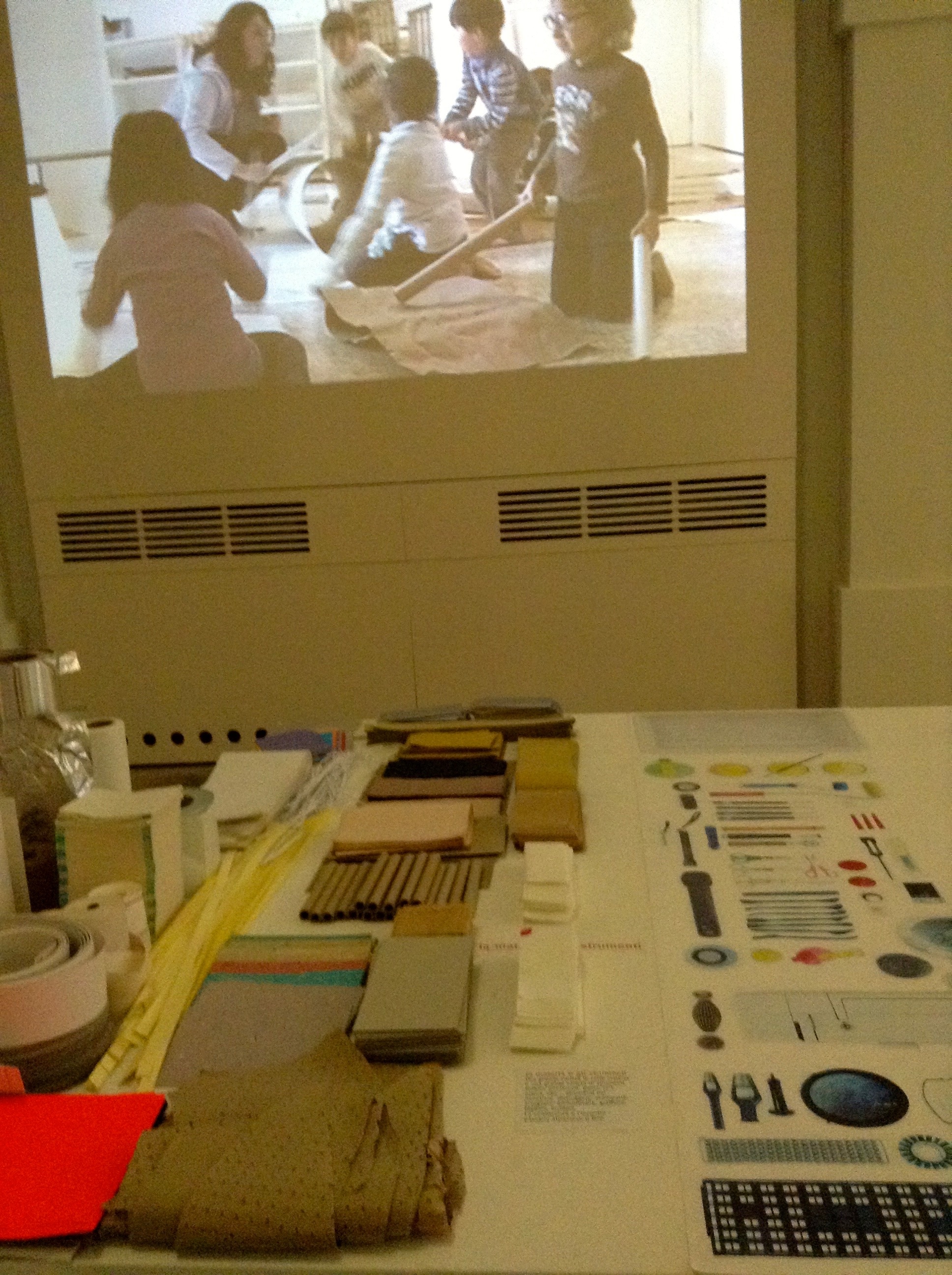

The Secrets of Paper was designed to explore the possibilities of paper. Walking into the room, it was jam-packed with every type of paper imaginable. The atelier exemplified the Reggio philosophy by creating an encounter with new materials, unguided exploration and discovery. Different textures and weaves of the paper often transformed when they came into contact with other “languages” such as light, photographs, moving images, or a webcam.

The Life of Living Organisms: Faded Beauty atelier consisted of a collection of nature objects in different stages of decomposition. This atelier focused on researching different phases in the life of a living organism. Our task was to explore different life stages of living organisms. We were given vegetables, fruits and plants, as well as various examination tools such as magnifying glasses, light tables or microscopes. We were then invited to reflect upon our explorations and discoveries through drawing, sculpting and photography. A variety of materials were available for us to use such as digital cameras, video cameras, and webcams. Those participating in this atelier came to a shared revelation that even decaying life was beautiful in its own way.

Through first-hand experience of working in these ateliers, I came to appreciate and respect the power of the small group to facilitate constructivist, artistic learning. I received a small glimpse of how children experience the Reggio school ateliers, in particular how atelier learning is a slow and careful education where children learn by trying out ideas, making mistakes, shifting thinking, and exploring materials at their own pace. The atelier experiences were designed to be pleasurable, yet children are encouraged to work diligently. During all of these atelier experiences I was struck by how the atelieristas gave us such genuine respect for our ideas and spirit of exploration. I also realized that the atelier is an unhurried educational experience, very different from the “learning outcome”–based education in America that is dominant today.